Monday, September 9, 2024 – Wednesday, October 30, 2024

After first visiting Sakhalin in 1996, Nitta Tatsuru began to visit the island regularly after 2010. Under the 1905 Treaty of Portsmouth, the southern part of the island was controlled by Japan and known as Karafuto. After the Soviet Union entered the war against Japan in 1945, Sakhalin became foreign territory, and many of the Japanese residents returned to Japan. Other colonial residents, however, lost their Japanese citizenship when Japan was defeated, and these people were stranded on the island. Nitta turned his camera toward ethnic Koreans (known in Russian as Koreyskiy) and their spouses, who were left behind after the war.

When Nitta met women on Sakhalin who spoke Japanese, he asked them, “Are you Japanese?” They answered, “No, we are Koreans who came here before the war,” a response that left a deep and lasting impression on Nitta, leading him to begin his frequent visits to the island. That journey was one of gazing at people and landscapes that have fallen into the deep ravines between nations, and of listening to the fading voices that echo there.

Nitta’s photographs depict women who have had nowhere to turn, forced to live suspended in the space between Japan, Korea, and the Soviet Union (now Russia). Captured in their tranquil frames are the layers of time these women have accumulated, as they placed their feet on the ground while at the mercy of the strong currents of history, as well as the unique environment of Sakhalin, where the traces of the era when it was Japanese territory are not easily dispelled. Please take this opportunity to view Nitta’s work, which has gained critical acclaim in recent years, including both the Hayashi Tadahiko Award and the Kimura Ihei Award last year.

Planned and organized by Kohara Masashi

Born in Fukushima Prefecture in 1967. After graduating from Tokyo Polytechnic University with a bachelor’s degree in engineering, Nitta joined Azabu Studio and later worked as an assistant to Hanzawa Katsuo. He went independent in 1996. For his photobook Sakhalin (Misha’s Press, 2022), a collection of images of stranded Koreans and Japanese living in Russian Sakhalin, and the accompanying exhibition Sequel to Sakhalin (Nikon Salon, Tokyo), he was given both the 31st Hayashi Tadahiko Award and the 47th Kimura Ihei Award. Solo exhibitions include Sequel to Sakhalin (Nikon Salon, Tokyo), Tokyo, and Mitaka City Gallery of Art); he also participated in the group exhibition Still Echo: Border Landscapes at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum.

Tatsuru Nitta

Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk(formerly Toyohara), 2011

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Kim Koushū(left)in her youth, with Chie Meguro, a classmate from advanced classes at Japanese elementary school, Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk(formerly Toyohara), 2010

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Kim Koushū at one of my earliest meetings with her, Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk(formerly Toyohara), 2010

Chromogenic print

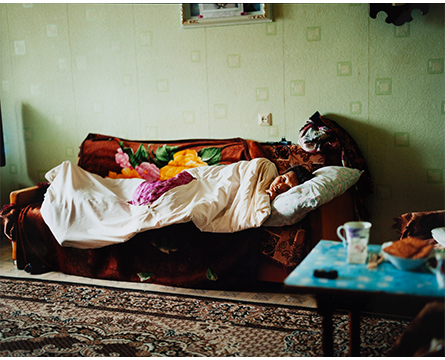

Tatsuru Nitta

Kim Koushū’s 84th birthday, Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk(formerly Toyohara), 2011

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Zagorsk(formerly Nishi-naibuchi), 2011

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Bykov(formerly Naibuchi), 2011

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Kim Koushū, Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk(formerly Toyohara), 2011

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

A ferry departing for continental Russia. After WWⅡ, many Japanese were repatriated to Japan from this port. Kholmsk(formerly Maoka), 2012

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk(formerly Toyohara), 2012

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

The remains of a “Houan-den” belonging to Touro Daiichi Elementary School, where Kim Koushū graduated from. Until the end of WWⅡ, all schools had a “Houan-den,” which was a small structure that housed a photograph of the Japanese emperor and emperss, and a copy of the Imperial Rescript on Education. Shakhtyorsk(formerly Touro), 2012

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Kim Koushū with her daughters, Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk(formerly Toyohara), 2011

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Kim Koushū, Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk(formerly Toyohara), 2012

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Kim Koushū looking for an old photograph, Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk(formerly Toyohara), 2012

Chromogenic print

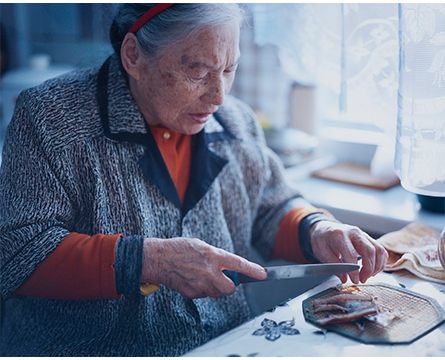

Tatsuru Nitta

Kim Koushū after finishing work in her field, Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk(formerly Toyohara), 2012

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Hatsuko Kimura, Aniva(formerly Ruutaka), 2011

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Aniva(formerly Ruutaka), 2011

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Hatsuko Kimura, Aniva(formerly Ruutaka), 2011

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Hatsuko Kimura fishing for tiny fish called chika, Aniva(formerly Ruutaka), 2011

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Hatsuko Kimura soon after being discharged from the hospital, Aniva(formerly Ruutaka), 2012

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

War-displaced Japanese from Sakhalin visiting Japan, Sapporo, 2017

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

“Is it warm outside?” Hatsuko asked me as she prepared to go out. “Would you like me to come with you?” I asked. “No. It’s just a short distance,” she replied as she left alone. Aniva(formerly Ruutaka), 2012

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Koushū’s third daughter Zina and great-grandson Lyonya(Vladik’s son)Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk(formerly Toyohara), 2014

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Kim Koushū, Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk(formerly Toyohara), 2012

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Ri Tomoko, Bykov(formerly Naibuchi), 2014

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Ruins of a Japanese monument to fallen soldiers, Shakhtyorsk(formerly Touro), 2014

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Shakhtyorsk(formerly Touro), 2014

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Hama-touro, Shakhtyorsk(formerly Touro), 2014

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Lena, Vladik’s daughter and Koushū great-granddaughter, Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk(formerly Toyohara), 2014

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Ruins of Higashi-shiraura Shrine, Vzmorye(formerly Shiraura), 2016

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Ri Tomiko and Sai Unbon, Dolinsk(formerly Ochiai), 2018

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Ri Tomiko, Bykov(formerly Naibuchi), 2016

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Dolinsk(formerly Ochiai), 2018

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Bykov(formerly Naibuchi), 2016

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Ri Tomiko, Bykov(formerly Naibuchi), 2017

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

On August 17, 1945, as Soviet troops approached, residents of Kami-shisuka were told to evacuate as officials set fire to the village. The charred remains of military buildings and homes dot the landscape. Ruins of the Imperial Japanese Army’s 88th Division, Leonidovo(formerly Kami-shisuka), 2016

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Korsakov(formerly Oodomari), 2023

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Ri Tomiko, Bykov(formerly Naibuchi), 2017

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Ruins of Oji Paper Co.’s Shiritoru factory, Makarov(formerly Shiritoru), 2017

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Northern Sakhalin was occupied by the Imperial Japanese Army from 1920 to 25, following the Nikolayevsk Incident, which involved members of the Russian Red Army killing residents. Alexandrovsk-Sakhalinsky, 2018

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Alexandrovsk-Sakhalinsky—best known from Anton Chekhov’s “The Sakhalin Island” —where approximately 4,000 Japanese and 1,000 Koreans resided under Japanese occupation. When the Japanese army retreated, most Koreans moved to Esutoru, Shiritoru, and other parts of northen Karafuto where they could play a role in modernization efforts. Alexandrovsk-Sakhalinsky, 2018

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

A river formerly called Shiritoru, Makarov(formerly Shiritoru), 2018

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

A field, which had been part of Bokujo no sawa, the farming community built for foreign residents of Karafuto near the end of the war Kamenetkaya(formerly Tonnai), 2018

Chromogenic print

Tatsuru Nitta

Tomiko singing, Dolinsk(formerly Ochiai), 2018

Chromogenic print